Justice William Musyoka’s scathing judgment in Tim Ndaguri Muiruri v Lynda Mkalama should surprise no one familiar with Milimani’s Small Claims Court. His blunt assessment that the “Small Claims Court project is failing” and no longer meets its founding objectives merely confirms what practitioners have been witnessing for months: the systematic destruction of what was once Kenya’s most innovative judicial institution. The rot can be traced to a single administrative decision that violated the law and strangled the court’s entrepreneurial spirit – the Chief Registrar’s choice in late 2023 to place the Small Claims Court under the supervision of the Magistrates’ Court Registrar, directly contravening Section 9 of the Small Claims Court Act.

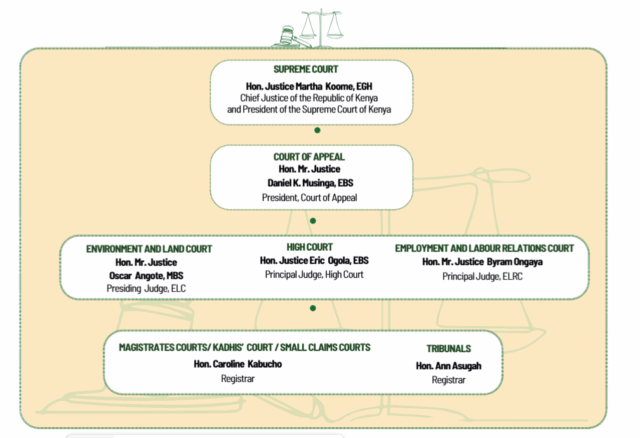

When the Small Claims Court Act was crafted in 2016, Parliament was deliberate in its design. Section 9 explicitly requires that the court be overseen by its own dedicated Registrar, who reports directly to the Chief Registrar – not through the hierarchy of the Magistrates’ Court. This wasn’t an oversight; it was recognition that the Small Claims Court needed administrative independence to fulfill its unique mandate of delivering justice within 60 days using innovative, simplified procedures.

Yet in a decision that can only be described as either grossly incompetent or deliberately sabotaging, the Chief Registrar chose to subordinate the Small Claims Court to the Magistrates’ Court Registrar. This single act of administrative disobedience has cascaded into every problem Justice Musyoka identified in his judgment. When you force an innovative institution designed for speed and flexibility into the bureaucratic straitjacket of traditional court administration, failure is not just predictable – it’s inevitable.

The effects were swift and devastating. Under the previous dedicated leadership of Hon. Stella Kanyiri’s tenure as Acting Registrar, the Small Claims Court had become a beacon of judicial innovation. It pioneered active case management, introduced e-filing for post-judgment requests, and consistently met its 60-day mandate. The court was living proof that Kenyan justice could be both fast and fair.

But the moment administrative control shifted to the Magistrates’ Court, this innovation died. Magistrates, trained in the slow, formal procedures of traditional courts, began imposing their familiar but incompatible methods on small claims proceedings. Instead of the flexible, inquisitorial approach the Act envisioned, cases devolved into mini-trials complete with excessive written submissions, multiple adjournments, and rigid adherence to civil procedure rules that the Small Claims Court was specifically designed to avoid. Judgments went from taking less than 60 days, to 6-12 months (even longer than Magistrate’s courts)

The statistics are damning but the numbers only scratch the surface. As someone who sat on the Bar Bench Committee, I witnessed firsthand the institutional rot that set in:

- Decrees taking months to publish: Despite the filing being fully electronic, it can take months to get a decree published, and then sometimes only after several visits to the registry or greasing palms. This is despite, the issue being brought up in ever single bar bench meeting since the courts were launched in 2021

- Unsigned warrants being enforced: I’ve experienced instances when court clerks, manipulate the system to publish Warrants of Attachement without proper judicial signatures. These are then passed on to auctioneers who enthusiastically enforce these unsigned Warrants, violating basic due process

- Costs assessed without statutory guidelines: There is criminal inconsistency in how costs are assessed. Instead of following the guidelines provided by the law, costs are made by court clerks without following the legal framework, creating arbitrary and inconsistent outcomes.

- Procedural chaos: The simplified procedures that made the court accessible has been replaced by the same complex civil procedure rules that clog regular courts. In one shocking instance, a magistrate asked me to return after 2 months in order to deliver an ex parte judgment, after I made a request for judgment in default of appearance.

These aren’t growing pains or isolated incidents. They represent the systematic abandonment of the Small Claims Court’s founding principles, replaced by the sclerotic practices of Kenya’s traditional judiciary.

When I raised these issues through proper channels – to the Chief Registrar, JSC, Deputy Chief Justice, and even the Judiciary Ombudsman – I was met with deafening silence. This isn’t mere bureaucratic sluggishness; it suggests either incompetence so profound as to be indistinguishable from corruption, or active complicity in the court’s destruction.

The response within the legal profession was equally telling. When I raised concerns at Bar Bench Committee meetings, I was silenced by “senior advocates” who warned I was being “rude.” At an adjudicators’ colloquia where I was invited by the Kenya Judiciary Academy to give a practitioner’s perspective, magistrates shouted me down as I was giving my presentation. On social media, I was corroborated by the public, but in private, magistrates threatened retaliation, promising unfavorable rulings if I continued speaking out. When I requested the Bar Bench Committee meet to address these issues, the committee simply refused to convene for several months. Eventually, faced with the unyielding and deeply entrenched rot, I chose to walk away, lest my brand be associated with what I could see was a sinking ship.

This wall of silence by those who would have made a difference speaks volumes. A functioning judicial system would welcome scrutiny and reform proposals. Instead, criticism of the Small Claims Court’s deterioration is treated as an attack on personal fiefdoms rather than legitimate concern for justice delivery.

The Small Claims Court was meant to democratize justice – to give ordinary Kenyans a forum where disputes under Ksh 1 million could be resolved quickly, cheaply, and fairly. It was designed to tackle one of Kenya’s greatest challenges: impunity. Small-scale theft, contract breaches, and commercial disputes that previously went unresolved due to cost and delay could finally find remedy.

Instead, the court has become exactly what it was meant to replace: a playground for those with connections and patience to game the system. Shylocks and unscrupulous creditors now use the court’s simplified procedures to flood the court with cases, and use the automatically generated 1st mention date to threaten their debtors. Meanwhile, legitimate claimants – small business owners, service providers, ordinary citizens seeking justice – find themselves trapped in the same procedural maze they thought they had escaped.

The human cost is captured in an anguished letter from one of my clients who wrote to the Judiciary complaining about a questionable judgment. Her company was denied payment for services rendered, and then denied justice by a curious dismissal of her claim based on a defence of “shoddy work” presented without any evidence. Some might ask “why not appeal”, the reason is because Section 38 of the Act largely prevents appeals based on understanding of evidence. It means that in a majority of cases, Small Claims Court judgments, however bad, are final. Her pain is captured lucidly in her letter where she writes – “I cry, I’m in pain” – this reflects not just one bad judgment, but the betrayal of an entire system that promised justice but delivered institutionalized theft. In her letter she asks whether magistrates are “compromised” and whether you need to “know people” to get justice, she’s articulating what many now believe: the Small Claims Court has been captured.

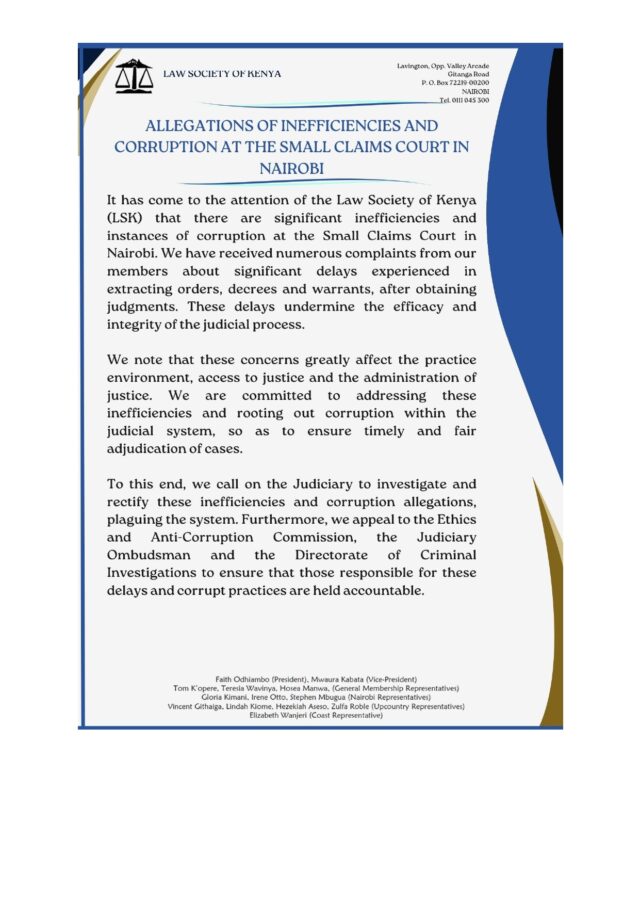

The transformation is complete. What began as Kenya’s most innovative court – one that proved justice could be both swift and fair – has been reduced to another feeding trough for judicial bureaucrats and their allies. The Law Society of Kenya’s formal complaint of 21st May 2024 about “significant inefficiencies and instances of corruption” at the Small Claims Court in Nairobi isn’t hyperbole; it’s documentation of institutional failure.

The appointment of magistrates as adjudicators, rather than the dedicated Adjudicators the Act envisioned, has been particularly destructive. These magistrates, comfortable with the glacial pace of traditional courts, see the Small Claims Court’s 60-day mandate not as a sacred obligation but as an inconvenient pressure. They’ve systematically dismantled the flexible procedures that made quick resolution possible, replacing them with the formal rigidity they know.

Against this backdrop, Justice Musyoka’s harsh assessment appears not as judicial overreach but as long-overdue truth-telling. His finding that determinations made outside the 60-day window are null and void isn’t harsh – it’s the inevitable consequence of institutional failure. When a court designed for speed consistently fails to deliver speed, its judgments lose legitimacy.

The judge’s observation that the Small Claims Court has “taken a trajectory” that brought it “on par with the Magistrates’ Court and High Court” – bogged down in formal procedures rather than focusing on substantive justice – is particularly damning because it describes exactly what Parliament sought to avoid. The court hasn’t failed despite good intentions; it has failed because those charged with implementing it chose to ignore both the letter and spirit of the law.

The question now isn’t whether the Small Claims Court can be reformed – it’s whether it should be completely reconstituted. The current system is so thoroughly compromised that incremental reforms will not suffice. What’s needed is wholesale change:

- Immediate Administrative Compliance: The Chief Registrar must immediately appoint a dedicated Registrar for the Small Claims Court as Section 9 requires, ending the illegal subordination to the Magistrates’ Court. This isn’t a suggestion; it’s a legal obligation that has been flouted for too long.

- Complete Staff Overhaul: The magistrates currently serving as adjudicators should be replaced with dedicated Adjudicators who will be trained to understand and embrace the court’s innovative mandate. The current crop has proven they cannot or will not adapt to the court’s requirements.

- Zero Tolerance for Delay: Any adjudicator who consistently breaches the 60-day mandate should face immediate disciplinary action. The timeline isn’t aspirational – it’s the law.

- Transparency and Accountability: All Small Claims Court judgments and accompanying decrees should be published online within 24 hours of delivery. The culture of secrecy that has allowed poor practices to flourish must end.

The Small Claims Court’s failure represents more than just one troubled institution. It’s a microcosm of how Kenya’s institutions can be captured and corrupted even when their founding vision is sound. The court was meant to prove that Kenya could deliver efficient, honest governance in at least one sector. Its destruction by administrative sabotage and professional self-interest sends a message that reform is futile, that innovation will always be smothered by entrenched interests.

But there’s still time to rescue this experiment. The legal framework remains sound – the Small Claims Court Act, properly implemented, can still deliver the justice revolution it promised. What’s required is the political will to enforce the law as written, regardless of whose bureaucratic territories are threatened.

Kenya’s Small Claims Court was meant to be a proof of concept that justice in Kenya could be swift, fair, and accessible. For a brief moment, it succeeded. But administrative sabotage, professional jealousy, and institutional capture have reduced it to another monument to mediocrity.

Justice Musyoka’s harsh verdict isn’t the problem – it’s the solution. By declaring late judgments null and void, he’s forcing a reckoning that the judicial leadership has tried to avoid. The choice now is stark: either restore the Small Claims Court to its founding vision by enforcing the law as written, or admit that even our most promising reforms cannot survive contact with Kenya’s institutional culture.

The entrepreneurs, small business owners, and ordinary citizens who believed in this court’s promise deserve better than bureaucratic excuses and judicial capture. They deserve the revolutionary access to justice that Parliament envisioned and that dedicated administrators like Hon. Kanyiri proved was possible. Whether they get it depends on whether Kenya’s judicial leadership chooses compliance with the law over comfort with the status quo.

The Small Claims Court can still be saved, but only if we’re honest about why it’s failing and who’s responsible for that failure. Justice Musyoka has provided that honesty. Now it’s time for action.